By Neil DeVotta

Dr. Neil DeVotta

Mark Salter, To End a Civil War: Norway’s Peace Engagement in Sri Lanka (London: Hurst & Company, 2015). 512 pages.

Ahmed S. Hashim, When Counterinsurgency Wins: Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). 280 pages.

Samanth Subramanian, This Divided Island: Stories from the Sri Lankan Civil War (Gurgaon: Penguin Books, 2014). 336 pages.

In May 2009, Sri Lanka’s armed forces comprehensively defeated the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The day after the war ended, Sri Lanka’s then President Mahinda Rajapaksa told parliament that his soldiers achieved victory by “carrying a gun in one hand, the Human Rights Charter in the other, hostages on their shoulders, and the love of their children in their hearts.”[1] The LTTE had used the very Tamils it claimed to protect as human shields, and the nearly three-decades-long conflict ended with over 300,000 people fleeing the LTTE-controlled area to government-controlled areas. The military did assist these fleeing Tamils, and some, no doubt, were carried to safety on some soldiers’ shoulders.

But this was no humanitarian operation. If anything, it was akin to what happened in Grozny when the Russian army flattened that city while combating Chechnya’s rebels and to what is now [October 2016] taking place in Aleppo, Syria. For Sri Lanka’s military wiped out the LTTE without differentiating between combatants and innocent civilians, going so far as to deliberately shell hospitals and the government’s designated No Fire Zones.[2] And it thereafter killed and disappeared numerous LTTE personnel and supporters who had surrendered even as it sent over 10,000 LTTE cadres into rehabilitation programs. The consequences of such scorched earth counterterrorism are now playing out, with a new government claiming to pursue reconciliation and accountability with the Tamil minority even as it fends off allegations of war crimes from the international community.

The Failure to Secure Peace

Sinhalese politicians have long failed to accommodate legitimate Tamil grievances, thanks to demographics, political opportunism, and a strident Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism. Starting in the mid-1950s, Sinhalese politicians belonging to the two main parties, the United National Party (UNP) and Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), took turns trying to outdo each other on who could best protect and promote the interest of the Sinhalese Buddhists.[3] With Sinhalese numbering nearly 75 percent and Buddhists being around 70 percent, such ethnic outbidding became a sad feature of the island’s politics. The majoritarian mindset was—and is—also helped by a Sinhalese Buddhist nationalist ideology, which claimed that Sri Lanka is the island of the Sinhalese and chosen repository of Buddhism; Sinhalese Buddhists have been ennobled to preserve and propagate Buddhism; minorities live there thanks to Sinhalese Buddhist sufferance; and they must, therefore, respect the majoritarian ethos. Within this context those who promoted a political settlement with the LTTE or advocated for devolution were branded traitors.[4]

The LTTE leadership understandably believed that no Sri Lankan government was going to deliver on its promises. That said, the LTTE was not genuinely interested in a negotiated settlement either, and its leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, was enamored with securing eelam (a separate Tamil state) through military means. The LTTE had used previous ceasefires to regroup and rearm. In short, the group blatantly manipulated ceasefires to pursue war, not peace.

Prabhakaran may have been a superb military strategist early on, but throughout the conflict he appears to have had little understanding of geopolitics. At the very end, whatever acumen he possessed of military strategy also seems to have deserted him; for he not only misgauged the Sri Lankan military’s buildup and capabilities, he also cavalierly exposed tens of thousands of Tamils to death while hoping for an international intervention that was not forthcoming.

The quest and failure for peace is what Mark Salter’s book focuses on, and it is a most useful account that has been compiled using the views and recollections of the major players (Sri Lankan, Indian, Norwegian and to a lesser extent American and other politicians and diplomats). Whether Salter’s goal was to exonerate the Norwegians—who were derogatorily called “salmon-eating busy-bodies” by Sri Lankans who felt they were biased towards the LTTE—is debatable; but it is indisputable that ultimately the Norwegian-led peace process failed because Sri Lanka’s two combatants were unable and unwilling to compromise on a political settlement.

Salter’s account shows how the Mahinda Rajapaksa government encouraged the Norwegians, who were merely facilitators and were therefore limited in what they could orchestrate, to stay on even as it vilified their role so as to appease Sinhalese Buddhist sentiment. Prior to becoming president, Rajapaksa had also told the Norwegians that he was not averse to reaching an agreement with Prabhakaran.

Many forget that Mahinda Rajapaksa was initially reluctant to restart a full-scale war with the rebel group, although his government began reinforcing the military and encouraged soldiers to assert themselves immediately after it came to power. The initial hesitance to take on the LTTE at a time when he rebels were violating the ceasefire more often than Sri Lankan forces may have partly been due to the secret agreement Rajapaksa’s campaign reached with the rebels, which prevented Tamils in the areas they controlled from voting in exchange for a large payment. Since Tamils mainly vote for the UNP during presidential elections, their being barred from the polls allowed Rajapaksa to win narrowly.

Salter’s interviews also suggest that the LTTE leadership was looking for a way to cooperate during the height of the conflict, and this no doubt had to do with the massive losses the group was facing. Prabhakaran was on record saying that his cadres could shoot him if he ever settled for an arrangement short of eelam. He did not settle, but neither was he capable of using the LTTE’s military prowess to deliver an advantageous political arrangement for the long-suffering Tamils. Today Tamils are a broken, bitter, and hagridden people who are worse off because Prabhakaran dared to pick up a gun.

One of Samanth Subramanian’s interviewees claims that during the last days of the war Prabhakaran distributed copies of the Hollywood movie 300, which depicts a group of Spartans fighting to their deaths against the Persians. If true, this was to prepare his cadres for the certain death that awaited them. Such fanaticism ultimately led to between 40,000 and 70,000 Tamils killed during the latter phase of the war (although these numbers are highly disputed by the Sri Lankan government) and that included Prabhakaran, his wife, and three children.

Subramanian’s book, simply put, is a splendid read. Well-crafted and balanced in its praise and criticism of both the Sinhalese and Tamils, it runs the gamut of recent Sri Lankan ethno-politics in a manner the uninitiated especially can appreciate. With over 98 percent of the Sri Lankan army being Sinhalese, it is hard today to fathom that around the 1950s and 1960s nearly 40 percent of the armed forces were Tamil. Subramanian’s interviews with a few Tamil military personnel who served during the civil war are therefore fascinating. A military (and bureaucracy) that is not representative of the population is a major sign of a country’s ethnic disparities. From that standpoint, Sri Lanka has a long way to go before Tamils (and Muslims too) can feel they are equal citizens.

Subramanian is Indian, and in that light one glaring lacuna in his book is the lack of focus on the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), which Rajiv Gandhi dispatched to Sri Lanka in 1987 as part of the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord and which ended up fighting the LTTE. The IPKF gets a mention here and there, but it is surprising that its activities are not discussed in any detail. Was this because the Tamils Subramanian interviewed were unwilling to offend him by recalling the IPKF’s malpractices? No doubt, the Indian military paid a stiff price by fighting India’s longest war against the LTTE, which at the time was a guerrilla organization. It is with good reason this Indian military fiasco is branded “India’s Vietnam.”

Given a few more months the Indian military might have defeated the LTTE, yet in the end it was the Indians who left in March 1990 (mainly because a new Sri Lankan government demanded the IPKF’s withdrawal). But the fact remains that up to that point, the worst atrocities Tamil civilians suffered were at the hands of undisciplined elements in the IPKF.[5] Many Sri Lankan Tamils continue to recall the IPKF within the context of the rapes and depredations they endured, unfair as that may sound to the upright and valiant Indian personnel who served and lost their lives in the island. This is why the LTTE claimed, truly or falsely, that by killing Rajiv Gandhi his assassin, Dhanu, was merely avenging her rape by IPKF personnel. This important aspect of the island’s history and Tamil experience merits better coverage.

The three books reviewed here note that one of the biggest mistakes the LTTE made was killing Rajiv Gandhi. No Indian government could thereafter deal with the organization and the Congress Party especially had ample reason to want the LTTE defeated. The Indians may have armed and trained some Tamil rebels in the early 1980s, but they even then were against a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka, lest that emboldened separatist forces within India. Yet geographic proximity and Tamil Nadu’s reaction to their ethnic cousins’ plight in Sri Lanka forced India to stay engaged and to be kept informed,[6] so that most foreign powers took no major initiatives regarding Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict without first briefing India.

It appears the LTTE leadership was led to believe that the Congress Party would lose the April-May 2009 general election in India and that a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government would pressure Sri Lanka to cease its military operations. The BJP did not win the 2009 general election, but Salter’s book shows how that possibility goaded Sri Lanka’s decision makers to try to defeat the LTTE before a new Indian government was installed. The ruthless tactics such timing dictated led to thousands of innocent Tamils getting killed.

Extirpation as Counterterror Strategy

In seeking to strengthen the military and improve its morale, the Rajapaksa government not only built on the narrative of the soldier being a war hero (ranawiriva), it also made clear that criticizing the military was not to be tolerated. Indeed, a number of journalists were attacked because they reported on the military negatively. This together with the glossy advertisement campaigns the government mounted led to military personnel even at the lower levels being feted in obsequious ways.[7]

The regime also increased the number of military personnel being recruited, which allowed the armed forces to hold on to territory captured from the LTTE (something it was not able to do previously). Furthermore, the government went shopping for sophisticated military hardware. That the Defense Secretary was the president’s brother helped in this regard, because armament costs and fear of an overly powerful military likely hindered such purchases in the past.

Many Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists and many in the military sincerely believe that the so-called eelam mindset threatens Sri Lankan sovereignty, and that fully eradicating it is sine qua non for the island’s security. This also meant eliminating the LTTE leadership without regard to human and material costs. Salter’s interviewees note that the order to liquidate LTTE leaders had to come from high up in the government. If so, the military carried out orders smacking of war crimes and thereby committed war crimes. This no holds barred, scorched earth strategy is also evidenced in Ahmed Hashim’s book. His is a commendable account of the politics associated with civil war.

Hashim is less interested in discussing the causes of the war (although he notes the scholarship of those whose work has sought to attribute causation) and more interested in trying to explain the nature of the LTTE and why it ultimately lost so badly. He says the LTTE best exemplified an outfit capable of waging hybrid war, given its capacity to combine terrorism, insurgency, and conventional war. He, however, does not emphasize how Prabhakaran’s infatuation with the latter ultimately undermined his strategizing.

Controlling territory and population helped with the LTTE’s conventional capabilities, for it allowed for voluntary and forcible recruitment and claims of de facto statehood status. Many were the Tamils ensconced abroad who pointed to the governing institutions the LTTE had set up and argued that eelam already existed; the international community merely had to recognize it. But the LTTE’s dedication to its de facto state and conventional warfare let the military know where exactly to target the group. And once the military had sufficient personnel, superior weaponry, and orders to disregard human casualties (irrespective of what was trumpeted in public), the LTTE’s days were numbered.

As Hashim points out, the main focus of the Sri Lankan military was to kill as many of the enemy as possible. Even before the endgame, there were reports that the Sri Lankan military was systematically bumping off Tamils suspected of being LTTE sympathizers.[8] It is, therefore, hardly surprising that the military went about eliminating hardcore LTTE cadres after they surrendered. Indeed, a U. S. State Department report to Congress that was released a few months after the conflict ended noted that thousands who were placed in Sri Lankan government-run camps following the war were “disappeared.”[9]

This was in addition to rape being “used as a tactic of war”[10] and military personnel burying alive Tamils who had sought shelter in makeshift bunkers. Killing off the leaders of a liberation movement or terrorism outfit is one of the best ways to extirpate it. And Sri Lanka’s politicians and military were determined to make the LTTE militarily acephalous. It was the reason they (based on credible evidence gathered thus far) also executed Balachandran, Prabhakaran’s twelve year old son after he was capturedalive alive. No heirs—and, hopefully, no future fires.

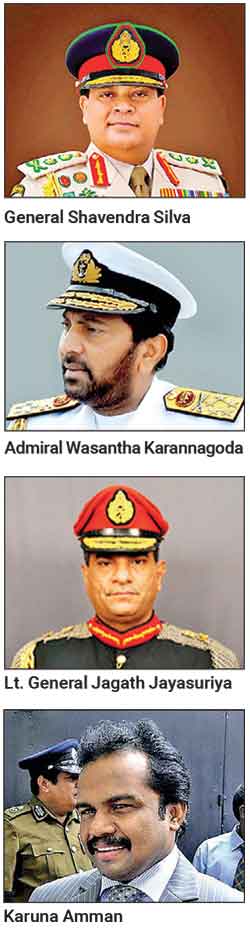

The new Sri Lankan government headed by President Maithripala Sirisena has promised to pursue ethnic reconciliation and accountability, but all indications are that it will fall short of ensuring especially the latter. For doing so would force it to implicate many who headed the government during the time of the LTTE’s defeat, and these include President Mahinda Rajapaksa, his brother and the then Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and former Army Commander Sarath Fonseka. Indeed, even President Maithripala Sirisena has been implicated since he on numerous occasions served as Acting Defense Minister.

An issue that complicates achieving transitional justice is the demise of nearly all LTTE personnel who engaged in war crimes. Their misdeeds can be documented further, but they cannot be punished. Thus the pursuit of accountability will end up being a one-sided affair, and there is simply no support for this among Sri Lanka’s majority Sinhalese. Neither is there support for the domestic-international hybrid courts the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has called for. Indeed, any politician who pushes for leading military personnel to be held accountable will get branded a traitor and be committing political suicide.

In this quest for reconciliation and accountability, certain Tamil politicians have not helped, given how their unrealistic demands have further hardened Sinhalese opinion. The upshot is that Sri Lanka’s accountability process is unlikely to lead to trials that threaten war crimes perpetrators with jail. Instead, it will most likely unfold in a manner similar to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation process sans retribution.

The rapid rise of China and India, and the Obama Administration’s so-called Pivot to Asia, have made Sri Lanka much more important from a geostrategic standpoint. During his tenure as president, Rajapaksa was happy to embrace China, because that country looked askance as he and his family unduly benefitted from Chinese-funded projects. Close ties with China also ensured that it shielded Sri Lanka at international forums on human rights even as Rajapaksa pursued authoritarian politics geared towards creating a political dynasty.[11]

Maithripala Sirisena’s victory has led to India, the United States, and the West enjoying closer ties with Sri Lanka even as the island pursues a more nonaligned foreign policy. Rajapaksa, however, continues to project himself as the military’s ultimate defender and wants to manipulate the transitional justice issue to recapture power. Aversion to such an outcome plus their geostrategic interests may push the West to settle for less on the accountability front.

Maithripala Sirisena’s government has moved the island away from the authoritarianism Rajapaksa sought to institute, but it too continues to appease the military at the expense of pursuing transitional justice. Since its independence in 1948, Sri Lanka’s politicians have missed numerous opportunities to salve the island’s ethnic wounds. The ongoing discourse and politicking surrounding transitional justice suggests it may be in the process of missing yet another opportunity.

Conflict Redux?

Of the three books reviewed, Subramanian’s is the only one that discusses how Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists have begun to target the island’s Muslims. The Muslims, who were depicted as the “good minority” due to their opposition to eelam and for generally siding with Sinhalese Buddhist preferences, have now been turned into the new “other.” During this author’s research in Sri Lanka in 2012, an interviewee said that right after the LTTE was defeated Mahinda Rajapaksa told some confidants that “now it was the turn of the Muslims.”

Rajapaksa and his government certainly colluded with anti-Muslim forces that sprang up once the civil war ended. These forces resorted to exaggerated and factitious accusations and operated with impunity as they attacked mosques, Muslim businesses, and certain homes (mainly in an enclave called Dharga Town, south of Colombo).

Nationalists obsess over demographics, and this is also the case with Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists. Subramanian’s account shows how Sinhalese nationalists claim that their community is “the fastest vanishing race on the face of this earth,”[12] despite the Sinhalese population having risen from 66.1 percent in 1911 to 74.9 percent in 2012 and Buddhist numbers having likewise gone up from 60 percent to 70.2 percent during the same period.[13] Pamphlets passed around by Sinhalese Buddhist extremists also claim that the Muslim are “breeding like pigs,”[14] which is part of a demonizing process that the Tamils too were subjected to during the period that led to the civil war.

There has long been an eddy of anti-Muslim sentiment on the island that the ethnic conflict helped mask. Mahinda Rajapaksa, who wrongly assumed he could win elections with only Sinhalese support, was eager to exploit this sentiment. Sri Lanka’s Muslims would most likely be in dire straits today had Rajapaksa not lost the presidential election in January 2015. For instance, one of the monks who led the anti-Muslim agitprop recently bemoaned that politicians were putting party ahead of country and “if these politicians only gave us a little backing we can end the rise of the Muslims.”[15]

Many in Sri Lanka are being influenced by the Islamophobia now trending globally. This suits Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists who thrive by harping against potential threats to nation and religion. The LTTE’s defeat has further emboldened them. Within this context, only a Pollyanna would bet against more ethno-religious strife in the island.

* Neil DeVotta is Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Wake Forest University. This review essay, which first appeared in Asian Security (March 2017), is reproduced with the publisher’s permission.

Notes

[1] Mahinda Rajapaksa, “This Victory Belongs to the People Lined Up Behind the National Flag,” The Island, May 20, 2019, at http://www.island.lk/2009/05/20/features4.html. Accessed October 15, 2016.

[2] All three books reviewed make reference to this and other war crimes perpetrated by the government and LTTE during the latter stages of the conflict. See also Gordon Weiss, The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers (London: The Bodley Head, 2011).

[3] Neil DeVotta, Blowback: Linguistic Nationalism, Institutional Decay, and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004).

[4] Stanley J. Tambiah, Buddhism Betrayed?: Religion, Politics, and Violence in Sri Lanka (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); H. L. Seneviratne, The Work of Kings: The New Buddhism in Sri Lanka (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Neil DeVotta, Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka, Policy Studies 40 (Washington, D.C.: East-West Center, 2007).

[5] See especially the details tabulated in Rajan Hoole, Daya Somasundaram, K. Sritharan, and Rajani Thiranagama, The Broken Palmyra: The Tamil Crisis in Sri Lanka—An Inside Account (Claremont, CA: The Sri Lanka Studies Institute, 1990).

[6] Madurika Rasaratnam, Tamils and the Nation: India and Sri Lanka Compared (New York: oxford University Press, 2016).

[7] Neloufer de Mel, Militarizing Sri Lanka: Popular Culture, Memory and Narrative in the Sri Lankan Armed Conflict (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007); Sandya Hewamanne, “Duty Bound: Militarization, Romances, and New Forms of Violence among Sri Lanka’s Free Trade Zone Factory Workers, Cultural Dynamics, Vol. 21, no. 2 (July 2009): 153-84.

[8] See, for instance, University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), Can the East Be Won Through Human Culling, Special Report, no. 26 (August 3, 2007), at http://www.uthr.org/SpecialReports/spreport26.htm. Accessed October 10, 2016.

[9] See, for instance, U. S. Department of State, Report to Congress on Incidents during the Recent Conflict in Sri Lanka (Washington, D. C.: U. S. Department of State, 2009).

[10] This was part of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s statement to the UN Security Council in October 2009. See Preeti Aroon, “Sri Lanka Anger over Clinton’s Rape Comment,” Foreign Policy, October 8, 2009, at http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/08/sri-lanka-angry-over-clintons-rape-comment/. Accessed October 16, 2016.

[11] Neil DeVotta, “China’s Influence in Sri Lanka: Negotiating Development, Authoritarianism, and Regional Transformation,” in Evelyn Goh, ed., Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 129-52.

[12] Samanth Subramanian, This Divided Island, p. 226.

[13] E. B. Denham, Ceylon at the Census of 1911 (Colombo: Government Printer, 1912); Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka, “Census of Population and Housing 2012,” at http://statistics.gov.lk/PopHouSat/CPH2011/index.php?fileName=Key_E&gp=Activities&tpl=3. Accessed February 15, 2016.

[14] Subramanian, This Divided Island, p. 226.

[15] Quoted in Colombo Telegraph, “‘With A Little Political Backing We Can End the Rise of Muslims,’ Gnanasara Who Wishes to Emulate Prabhakaran Declares,” September 21, 2016, at https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/with-a-little-political-backing-we-can-end-the-rise-of-muslims-gnanasara-who-wishes-to-emulate-prabhakaran-declares/. Accessed September 29, 2016.