UK moves on Sri Lankan accountability

The British government has announced that it is placing sanctions on a four individuals alleged to have command responsibility for crimes committed during Sri Lanka’s civil war (1983 – 2009). The group of those alleged to be responsible for war crimes are all high ranking military figures: three commanders from the Sri Lankan armed forces, the other a former Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) leader turned government supporter. Further details are provided in the DailyFT article reproduced below.

While the British move’s practical effect is likely to be small, its wider potential political impact is considerable. First and foremost, the principle of universal jurisdiction can be applied to these alleged war crimes perpetrators by one country, why can’t others follow suit? Either way, the move brings these four military commanders closer to a reckoning with their in many cases egregious alleged crimes than anything that’s issued to date from the domestic Sri Lankan judicial system, whose systemic weaknesses with respect to accountability are all too well known.

UK sanctions several responsible for HR violations and

abuses during Sri Lankan civil war

Tuesday, 25 March 2025 04:37 – – 1119

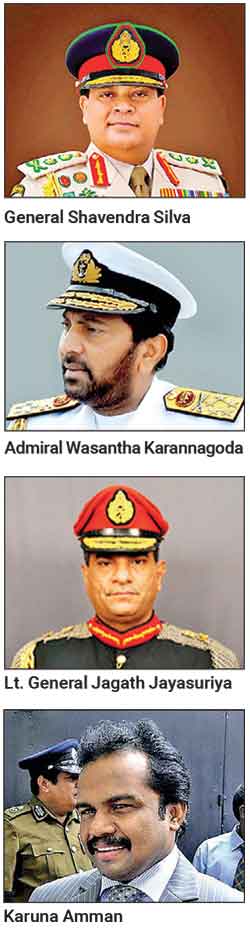

- Shavendra Silva, Wasantha Karannagoda, Jagath Jayasuriya and Karuna Amman in the dock

- Measures include UK travel bans and asset freezes

- UK says committed to working with new SL Govt. on human rights

- Welcomes commitments to national unity

The UK yesterday sanctioned figures responsible for serious human rights violations and abuses during the civil war in Sri Lanka.

The UK said sanctions have been imposed on former Sri Lankan commanders and an ex-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) commander responsible for serious human rights violations and abuses during the civil war and said sanctions aim to seek accountability for serious human rights violations and abuses committed during the civil war and prevent a culture of impunity.

The UK Government has imposed sanctions on four individuals responsible for serious human rights abuses and violations during the Sri Lankan civil war, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and/or perpetration of sexual violence.

The individuals sanctioned by the UK include former senior Sri Lankan military commanders and a former LTTE military commander who later led the paramilitary Karuna Group, operating on behalf of the Sri Lankan military against the LTTE.

Those sanctioned are: former Head of Sri Lankan Armed Forces Shavendra Silva, former Navy Commander Wasantha Karannagoda, former Sri Lanka Army Commander Jagath Jayasuriya, and former military Commander of the terrorist group LTTE Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan. Also known as Karuna Amman, he subsequently created and led the paramilitary Karuna Group, which worked on behalf of the Sri Lanka Army.

The measures, which include UK travel bans and asset freezes, target individuals responsible for a range of violations and abuses, such as extrajudicial killings, during the civil war.

Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs State Secretary David Lammy said: The UK Government is committed to human rights in Sri Lanka, including seeking accountability for human rights violations and abuses which took place during the civil war, and which continue to have an impact on communities today. I made a commitment during the election campaign to ensure those responsible are not allowed impunity. This decision ensures that those responsible for past human rights violations and abuses are held accountable.”

“The UK Government looks forward to working with the new Sri Lankan Government to improve human rights in Sri Lanka, and welcomes their commitments to national unity,” Lammy added.

During her January visit to Sri Lanka, Minister for the Indo-Pacific MP Catherine West held constructive discussions on human rights with the Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, civil society organisations, as well as political leaders in the north of Sri Lanka.

UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office said for communities to move forward together, there must be acknowledgement and accountability for past wrongdoing, which the sanctions listings introduced today will support.

“We want all Sri Lankan communities to be able to grow and prosper. The UK remains committed to working constructively with the Sri Lankan Government on human rights improvements as well as their broader reform agenda including economic growth and stability. As part of our Plan for Change, the UK recognises that promoting stability overseas is good for our national security,” it added.

The UK has long led international efforts to promote accountability in Sri Lanka alongside partners in the Core Group on Sri Lanka at the UN Human Rights Council, which includes Canada, Malawi, Montenegro, and North Macedonia.

The UK has supported Sri Lanka’s economic reform through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, supporting debt restructuring as a member of Sri Lanka’s Official Creditor Committee and providing technical assistance to Sri Lanka’s Inland Revenue Department.

The UK and Sri Lanka share strong cultural, economic, and people-to-people ties, including through their educational systems. The UK has widened educational access in Sri Lanka through the British Council on English language training and work on transnational education to offer internationally accredited qualifications.

https://www.ft.lk/front-page/UK-sanctions-several-responsible-for-HR-violations-and-abuses-during-Sri-Lankan-civil-war/44-77474